A version of this piece was published in the Hollywood Fair journal, August 2016 (pp 40-45). I am currently working on a more comprehensive article.

Once again we are on the eve of Punchestown. To-morrow will be the opening day of the great steeplechase meeting which is held annually under the auspices of the Kildare and National Hunt Stewards, and which in years past was favoured with the patronage of Royalty and the élite of many countries. The gathering at Punchestown has always been representative of the higher class lovers of sport, and in their ranks beauty and fashion invariably held prominent place. On the present occasion the races, like much else, suffer considerably as the result of the war.

As indicated in the above Irish Times article, the Punchestown Festival of 11-12 April 1916 not only occurred during Lent, but also took place during the second year of World War I, which had broken out in late July 1914. The festival therefore took place under the atmosphere of the ‘Great War’, which many had believed would have been over by Christmas 1914, a fact demonstrated by the war diary of Captain Norman Leslie, from Castle Leslie, Co. Monaghan, a soldier fighting in the British Army: ‘I prophesy the war will be over by the middle of November – we shall get home by December, at least the happy survivors!’. While many individuals engaged in numerous, various, and important, ‘war efforts’, many aspects of life, including social and sporting activities, continued during the war, albeit on a less extravagant basis. Theatre, football and horse racing fell into this category, and provided enjoyable activities for many throughout the war period. This article will examine the Punchestown Festival of 1916, a year in which Ireland not only suffered the effects of a world war, but also experienced the Easter Rising, which took place less than two weeks after the Festival. By focusing on the continuation of racing during World War I, the introduction of taxes on the sport, as well as the efforts to attract the custom of potential race goers to shops, public transport and, indeed, the races, an insight into the 1916 Punchestown Festival, which took place during a world war and in the lead up to an insurrection to end British rule, will be gained.

Racing in Ireland suffered many impacts of the ‘Great War’. Between 1913 and 1918 Ireland experienced a decrease in both the number of race courses and race meetings. Race days decreased from 122 to 85, with the race meetings dropping from 89 to 56. The number of racing venues also reduced from 54 to 24 during the same period, a decrease which partly stemmed from the fact that the racecourses at Fermoy and The Curragh were ‘acquired for military purposes’. In addition, racing also received attention from the British Government and British War Office on a number of occasions during the war. For example, the War Office called for the cancelation of all horse racing, except at Newmarket, while racing was also banned in Britain for a brief period in May and June 1917. The relative shortness of the period in question was due to the realisation of ‘the general economic importance of racing as an industry and source of employment’, and, as a result,forty days’ racing was permitted in England, increasing to 80 in 1918. While a similar plan had been suggested for Ireland, it was never implemented, with the Irish stewards releasing a statement that ‘conditions’ which led the Jockey Club to restrict racing in Britain ‘did not affect’ Ireland.

Horse racing therefore continued in Ireland, and proved popular with the Irish people during the war years. However, the sport was impacted by the British Government’s introduction of both the Excess Profits Duty under the 1915 McKenny Budget and the 1916 Entertainments or Amusements Tax, which effected Irish racing until the 1920s. The Excess Profits Duty introduced ‘a 50% levy on profits in excess of pre-war levels’, being increased to 60% in 1916 and 80% in 1917. According to Fergus D’Arcy, Department of Finance papers noted many racecourses ‘also found the tax bearing directly upon them’, a fact which likely continued until 1921, the year to which the Excess Profits Duty was charged. Horse racing was additionally impacted by the introduction of the Entertainments or Amusements Tax. In early April 1916, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Reginald McKenna, ‘proposed a new tax on “tickets for entrance fees charged on amusements, such as theatre, cinema, football matches, [and] horse racing.”’ The Chancellor believed such a ‘duty’ would raise almost £22 million per annum ‘by charging ½d. on admission fees up to 2d.’, with the duty increasing from that point. As with other public amusements, including concerts, recitals, lectures, readings, cinemas, dancing and games, including football matches, the admission fee to race meetings was subject to the levy introduced by the tax placed on admittance fees.

Despite the introduction of and discussion regarding taxes and duties targeting sport, reports on the 1916 Punchestown Festival were numerous in both the local and national press, although World War I still featured heavily. This can be observed in an Irish Times article in which the impact of the war upon the Festival in April 1916 was highlighted:

Punchestown, owing to the war, was not itself yesterday. There were, of course, the crowd, the bustle, and the gaiety that are always to be found at the Kildare and National Hunt Race Meeting, but the genuine spirit of Punchestown was lacking. This could easily be seen by a glance at the Club enclosure, and by the absence of the house parties usually associated with the meeting, while the fact that military officers have now something more serious to do than dispense their usual hospitality at Punchestown also brought about a noticeable change. The war has, in fact, altered completely the spirit of Punchestown. On every side its effects could be seen. The subdued shades of the ladies’ dresses, the prevalence of khaki uniforms of officers, occasionally interspersed with those of naval men on leave, and the on leave, and the presence of numerous soldiers from the Curragh garrison getting ready for the trenches showed that the war has had a great influence on racing gatherings.

Although those attending the Punchestown Festival included several officers on leave from the war, reference was made by one journalist to the fact that many people who were mourning the death of family members and friends of those who were fighting and killed in the Great War would not be attending the race meeting. It was the absence of such friends and family members, as well as those who had volunteered for and were fighting in the war, which resulted in a decrease in attendance at the Festival. This was noted in the Sporting News, where the impact of the war was highlighted. It was stated that much of the entertaining, which the author notes ‘was such a conspicuous feature of the gathering in pre-war days’, would not go ahead as they had done before the outbreak of World War I.

| PUNCHESTOWN RACES, TUESDAY and WEDNEDAY APRIL 11th and 12th. ADMISSION TO STAND. REVISED CHARGES. Double-Day Ticket …………………. £1 0 0 Single-day Ticket ……………………. 0 15 0 |

Although many people were not in a position to attend the Festival due to bereavement, those who were able to attend the festival recorded their day at the races. This included James Finn whose plans to attend the races are recorded in a letter he wrote to May Fay, thus highlighting that businesses provided their staff with a day’s leave to go to Punchestown Festival:

Punchestown is on for two days you know and we always get an office holiday for the races, half of the staff going one day and the other half on the second day. Result is that both yesterday and today were very quiet and so far as wish is concerned I might as well be off.

As demonstrated by the fact that Finn was given a day off for the racing, it can be observed that the Punchestown Festival was an entry on the social calendar, along with the Dublin Horse Show Week. Indeed, on 10 January, the Irish Times noted that ‘Dublin still has Punchestown season’, highlighting that the Festival was going ahead despite the on-going war.

Businesses were also eager to take advantage of the Punchestown Festival in the hope of attracting footfall for ‘gala’ events. As a result, many larger shops in Dublin, including Kellett’s, Holmes’, Robert & Co., and Switzer’s, all located in the city centre, placed large and detailed advertisements regarding clothes such as ‘Charming Silk Model Costumes and Gowns’, in the Irish Times and its ‘Fashion Intelligence’ section. Also appearing on Grafton Street, though this time at West and Son Jewellers, Grafton House, were a number of cups presented for well-known and popular races at the Punchestown Festival. These included the National Hunt Cup, the Kildare Hunt Cup, the Tickell Challenge Cup and the Bishopscourt Cup, the latter of which was a gold challenge cup presented by the Earl of Clonmel. In addition to the effort made by shops and jewellers for the Punchestown Festival, theatres, hotels and sporting organisations also attempted to attract customers during the Festival. These included the Gresham Hotel at which Mr and Mrs Leggett Byrne held a dance on 11 April under the patronage of the Dublin Fusiliers Central Advisory Committee in order to raise money for ‘the Kildare Prisoners of War Fund’, and a Flag Day in aid of the Disabled Soldiers’ Bureau also took place at Punchestown in April. In addition to the dance, a number of boxing ‘Punchestown Week Contests’ were held in the Ancient Concert Room on the same day. Events such as these, in addition to the advertisements regarding new and suitable attire available for purchase for the races, demonstrate that the Punchestown Festival was a highlight in the social calendar and that people travelled from across the country to attend the race meeting.

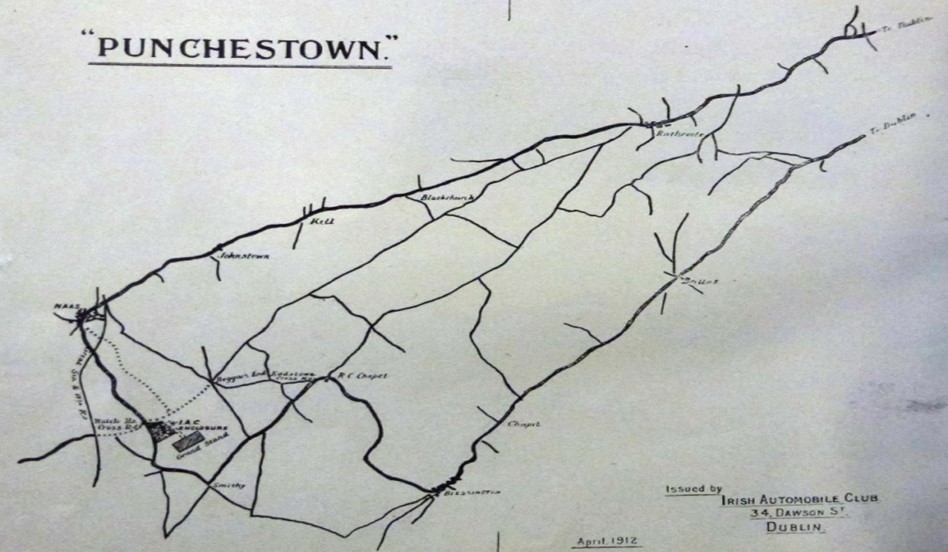

Many of those attending the Punchestown Festival travelled via public transport. Transport to the races featured in newspapers, with the publication of many advertisements regarding the varying modes of transport available in the run up to the Punchestown Festival. In addition to detailing the special and nationwide race day trains, timetables and ticket prices, the fact that ‘cattle train[s]’ would not run as usual was highlighted. However, anyone who wished to transport horses from Dublin or intermediate stations, the possibility of a ‘special train leaving Kingsbridge at 9.30am, returning from Naas after departure of last Passenger Special’ was advertised, thus ensuring transport to Punchestown for those who needed it. Others opted to drive or be driven to the race meeting, a fact expected by Punchestown. In preparation for the cars arriving to the racecourse, a number of notices were published in the classified advertisement section of the national papers to highlight the traffic arrangements for the race meeting. For the 1916 Punchestown Festival, it was noted that cabs and hackney cars, such as the Motor Char-A-Bancs, were to veer left following their entry to the racecourse, drop their passengers at the Paddock Gate Enclosure and then turn left ‘on to the field’. In contrast, those with Kildare Hunt Carriage Enclosure Tickets who arrived by private cars or hackney carriages were to turn right the after entering Punchestown, pass the back of the Hunt Stand and park in the relevant enclosure. The advertising of these directions for cars and carriages highlights the crowd expected for the Punchestown Festival.

The 1916 Punchestown Festival took place during World War I, which had been on-going for just under two years. While many people were able to attend the race meeting, including business employees and soldiers who were on leave, it should be noted that others did not attend due to family members being killed on the front. While Dublin shops actively advertised their fashions in a bid to attract customers planning on attending the Festival, and organisers of Dublin entertainment events publicised the details in the media, attendees to the races were impacted by the British Government’s introduction of the Excess Profits Duty. Nonetheless, despite the challenges posed by taxes introduced due to the war, the Punchestown Festival was ‘held as usual’. Despite the challenges and difficulties imposed by World War I, the 1916 Punchestown Festival, famous for its banks races, was thronged with crowds who travelled, and contributed to the ‘bustle, and the gaiety that are always to be found the Kildare’ racecourse.